Once again visiting the 1980’s, just because the decade was such an exciting time to be a comics reader (or arguably a comics creator). The big two comics companies had emerged from the chaos of the late 70’s with a stable of exciting new talents and a new emphasis on more mature storylines. Production standards had taken a huge leap in quality with the introduction of better paper and full-process color printing. And independent comics were enjoying a huge leap in sales, thanks to the rise of the direct market and the success of pioneers like Dave Sim’s Cerebus and Elfquest by Wendy and Richard Pini. Independent publishers like Pacific Comics and Eclipse Comics were allowing creators to keep the rights to their properties, which prompted the big two to offer enticements like bonuses and royalties and the return of artwork.

Once again visiting the 1980’s, just because the decade was such an exciting time to be a comics reader (or arguably a comics creator). The big two comics companies had emerged from the chaos of the late 70’s with a stable of exciting new talents and a new emphasis on more mature storylines. Production standards had taken a huge leap in quality with the introduction of better paper and full-process color printing. And independent comics were enjoying a huge leap in sales, thanks to the rise of the direct market and the success of pioneers like Dave Sim’s Cerebus and Elfquest by Wendy and Richard Pini. Independent publishers like Pacific Comics and Eclipse Comics were allowing creators to keep the rights to their properties, which prompted the big two to offer enticements like bonuses and royalties and the return of artwork.

And right in the middle of this ferment, in 1984, comic book legend Neal Adams decided to launch his own comics company, Continuity Publishing, with the anthology title, Echo of Futurepast (you will see this title listed as “Echo of Future Past” some places, like on Adams’ own website, but the indicia listed “Futurepast” as one word).

Echo was an anthology title in the vein of Heavy Metal and Epic Illustrated, featuring lush fully-colored artwork and often incomprehensible stories. In fact, at least one of the features in the first issue had previously appeared in a slightly different form in Heavy Metal. At a $2.95 cover price, Echo of Futurepast was extraordinarily expensive, but it featured high-quality paper (the second issue is printed on the same kind of glossy paper you saw in high-end magazines) and full-process color. Unfortunately, the coloring itself was inconsistent. And if the book hadn’t featured reprinted material for around half its contents, it might have been even more expensive.

Leading off the first issue was “Bucky O’Hare,” a funny-animals-in-space feature written by Larry Hama (perhaps best known for his long run writing Marvel’s G.I. Joe) with art by fan favorite Michael Golden. You may notice some similarities between Bucky and Marvel’s Rocket Raccoon, who starred in a Marvel miniseries the next year and will be featured in Guardians of the Galaxy, one of the big-screen Marvel epics due out next year. However, Rocket Raccoon actually came out first, debuting in 1976.

Bucky O’Hare is the captain of the Righteous Indignation who along with his crew–Dead Eye Duck , Bruce the Betelgeusian Berserker Baboon, Blinky the robot, and Jenny the Witch Cat or something–come under attack from the evil toads. During the attack, engineer Bruce is vaporized while trying to repair the photon accelerator that is the ship’s only hope of survival.

Luckily, on Earth, young Willy DuWitt activates a photon accelerator that he has built in his bedroom from household junk, which creates a hyperspace portal to the Righteous Indignation. So Willy decides to gives the crew a hand.

Bucky O’ Hare was the most successful of the Continuity-published properties, being reprinted a couple of times in graphic novel form and somehow spawning a short-lived animated series and toy line. However, the odd and all-too-brief storyline was not helped by the artwork. I love Golden’s work, but this is my least favorite of his projects by far, and not because it’s a funny animal story. Golden swamps every panel with extraneous detail that ends up getting lost under the muddy colors. It’s physically hard to read.

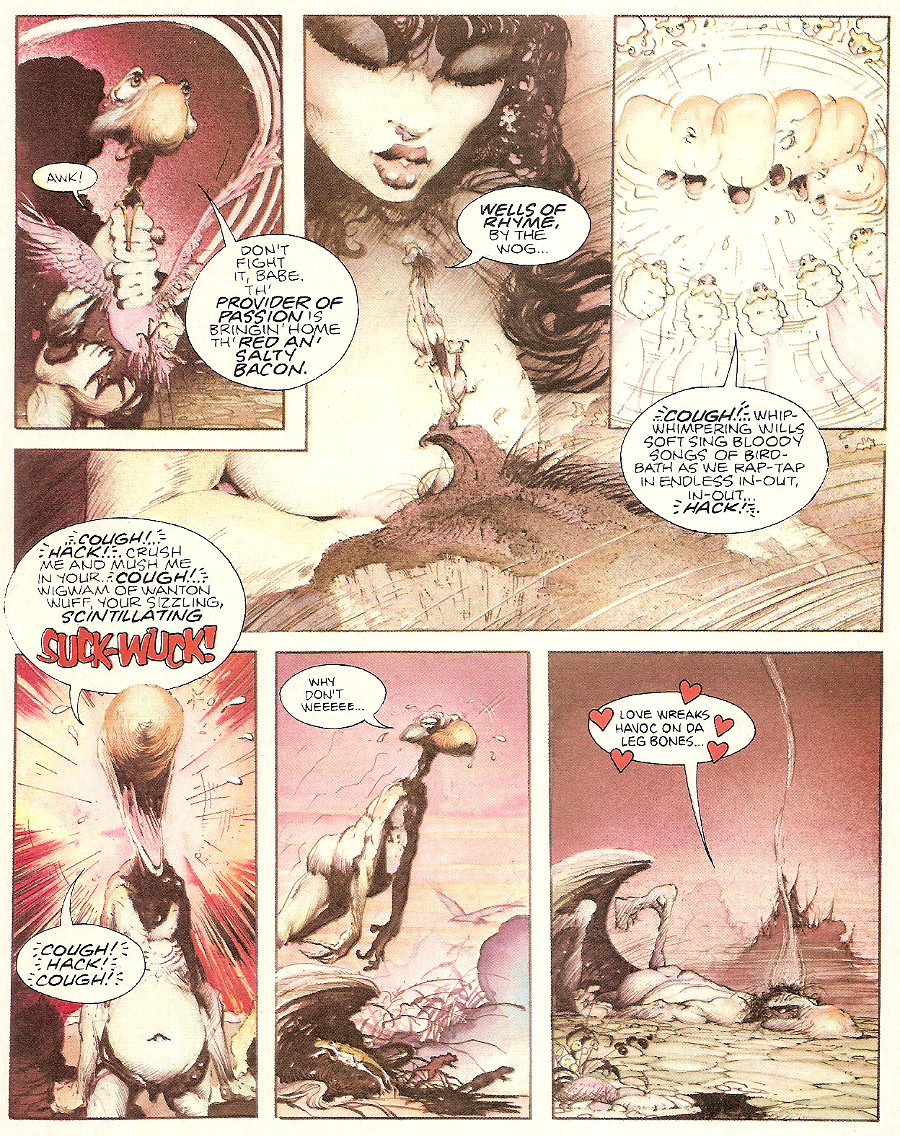

Another fan-favorite artist featured is Arthur Suydam. Suydam’s lush artwork, which combines many influences including Frank Frazetta and Arthur Rackham, graces “Mudwog” (listed in the contents as “Mudwogs,” although the artwork on the actual stories always uses the singular) and I use the term “graces” completely ironically, because there is nothing graceful about the story, some of which first appeared in Heavy Metal. The story is a combination of gutter humor and Warner Brothers-style slapstick, with utterly incomprehensible dialogue.

Later issues feature such laff-riot material as a giant pissing on Lilliputians, a slapstick rape, and Mudwog diving into the giant’s penis to be attacked by a horde of carnivorous ambulatory sperm. You have to read closely to get some of the sight gags, however, because Suydam’s muted coloring, while gorgeous, often conceals details.

A third story featured a character called “Virus.” Featuring static photocopied artwork, the “story” features a series of encounters between innocent strangers and “the human infection called Virus.” Basically, he’s that dude you meet at parties sometimes, who every time you talk to him, you wish you hadn’t. I have no idea why Adams thought we would want to read stories about other people having to deal with that dude. Thoroughly unpleasant, without even the saving grace of decent art.

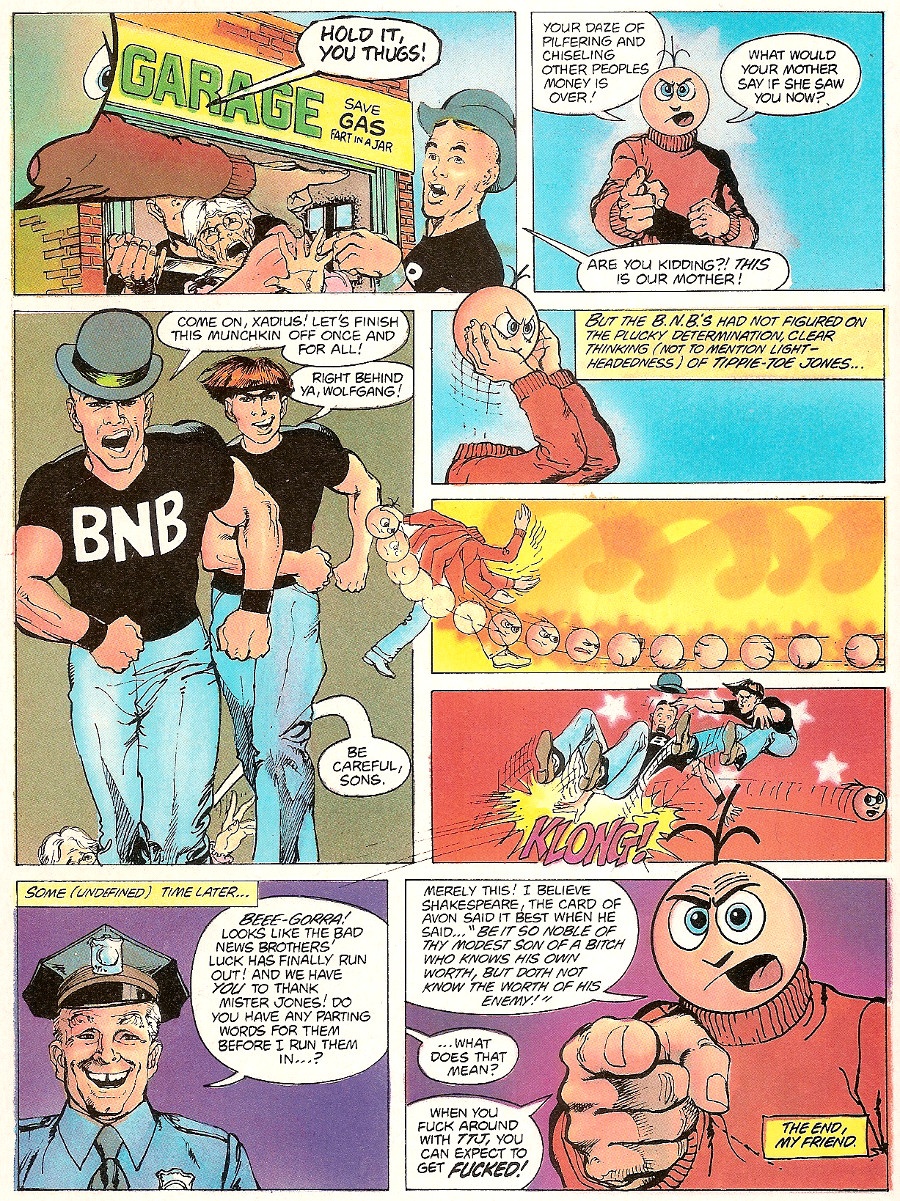

A fourth feature that appeared once in the first issue and then disappeared for several issues was “Tippie Toe Jones.” This was a really weird series that followed the curious 80’s custom of placing a cartoonish character (like Cerebus the Aardvark) in a realistic world alongside realistic people. The art was credited to Louis Mitchell, although it looks a lot like Neal Adams’s own work (Adams finally gets an inker credit by Tippie’s third appearance).

The joke (I guess) was that although Jones looked like the real-world version of a drawing scrawled by a five-year-old, he was cynical and foul-mouthed. Unfortunately, there was no story substance at all. Some sample panels in the first issue illustrated Jones with a tin man and scarecrow in an obvious rip-off of The Wizard of Oz, but I don’t know if that storyline was ever published. I had given up on the title by then.

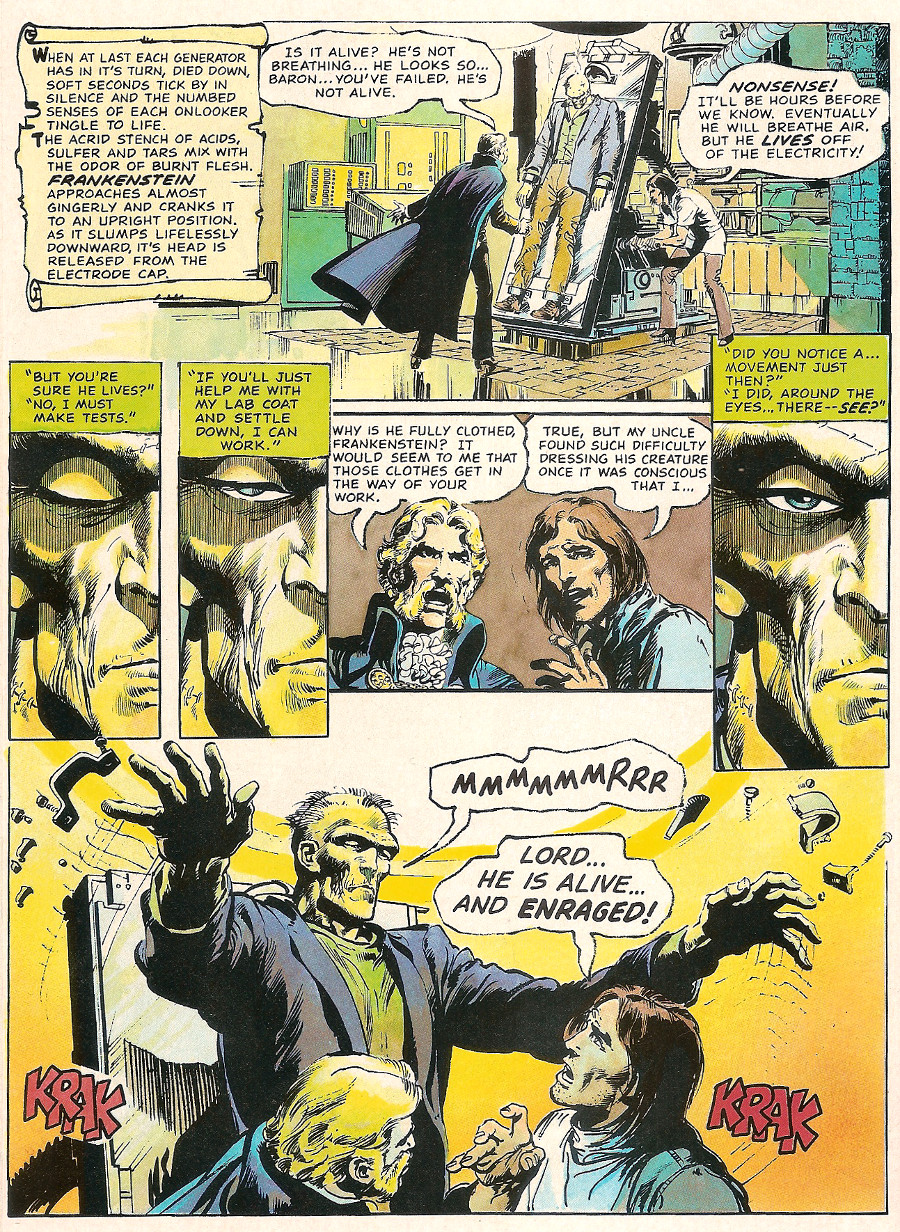

And then there was the centerpiece of the first five issues, Neal Adams’s epic “Frankenstein-Count Dracula-Werewolf.” This had originally been published as part of a comic-book-and-record set by Power Records, which had done a lot of audio versions of various superheroes during the 1970’s. The story, which was apparently also written by Adams, tells of young Vincent, nephew of the Baron Von Frankenstein, who is forced to flee angry villagers with his fiancee Ericka. They find shelter in the castle of Prince Vlad, who then holds Ericka hostage in order to force Vincent to create a new monster to serve the prince.

And so the monster rampages, Ericka is turned into a werewolf, and Prince Vlad is revealed to be Dracula, who dies in a titanic struggle with the monster. The story is in one sense the best of the early issues, in that it is at least comprehensible, but it’s also the most conventional and pedestrian (and suffers from Adam’s idiosyncratic overuse of ellipses).

Later issues featured reprints of European stories unfamiliar to American audiences, like Carlos Gimenez’s “Hom” and “Torpedo 1936,” by Enrique Sanchez Abuli and Alex Toth. Echo of Futurepast expired after nine issues, after problems with inconsistent quality (this is not the first Continuity comic I’ve featured that printed pages out of order, for example), poor editing, and mediocre stories.

I remember being excited by the book when it first came out. I was a huge Adams fan, and loved the idea of an anthology featuring work that rose to his level. But after six issues, I wasn’t seeing it. Several of the features looked great, but the stories were just no fun to read. So I hung it up.