If you were to ask me what the best comic in my possession is, I would be hard pressed to answer. There are so many I like for so many different reasons. But if you were to ask me about the worst, this would be it, hands down. In fact, I debated for months about including this comic in Out of the Vault, just because it’s so bad that it doesn’t seem worth wasting time and energy on. I ultimately decided to include it out of historical interest. I’ll get to the history in a bit.

If you were to ask me what the best comic in my possession is, I would be hard pressed to answer. There are so many I like for so many different reasons. But if you were to ask me about the worst, this would be it, hands down. In fact, I debated for months about including this comic in Out of the Vault, just because it’s so bad that it doesn’t seem worth wasting time and energy on. I ultimately decided to include it out of historical interest. I’ll get to the history in a bit.

The comic in question is Jontar #2, dated June 1986 from Mature Magic Publications. Just one glimpse lets you know that this is an amateur publication. Instead of the glossy cover and pulp paper of a normal comic book, the comic is printed in black-and-white on very white bond paper, like any normal book or pamphlet. The cover is printed in only two colors on the kind of heavy parchment paper you see on cheaply printed pamphlets. Text features on the inside covers (copyright notice, notes from the publisher and artist, and reader letters) are typewritten rather than typeset. The entire product screams “cheap.”

Except for the price, that is. Notice the cover price of $1.75. For comparison, a regular monthly issue of Batman, with a comparable number of story pages, printed in color with completely professional production values (though on cheap pulp paper), cost 75 cents, less than half, while a prestige product like Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, 64 pages of full-color on white, heavy Baxter paper with full-bleed color on the cardstock covers, cost $2.95. For the record, though, I paid exactly $0.00 for this issue.

So, let’s take a look at Jontar #2, “Camel Gold,” written by Bill W. Miller and drawn by Dane Barrett . The issue begins with a two-page recap of issue #1 (originally drawn by Tony Lorenz) which is described in some detail here. Note that even though he’s from the U.S. in the modern-day, Jontar’s name is not a contraction of Jonathan Tarr or anything tropey like that. Nope, his dad named him Jontar because he was a big fan of sword-and-sorcery novels and wanted his son to have a cool-ass barbarian name. If you think that sounds a little white-trash, I’ll have you know that Jontar grew to become a respected garbageman and exotic dancer, so there.

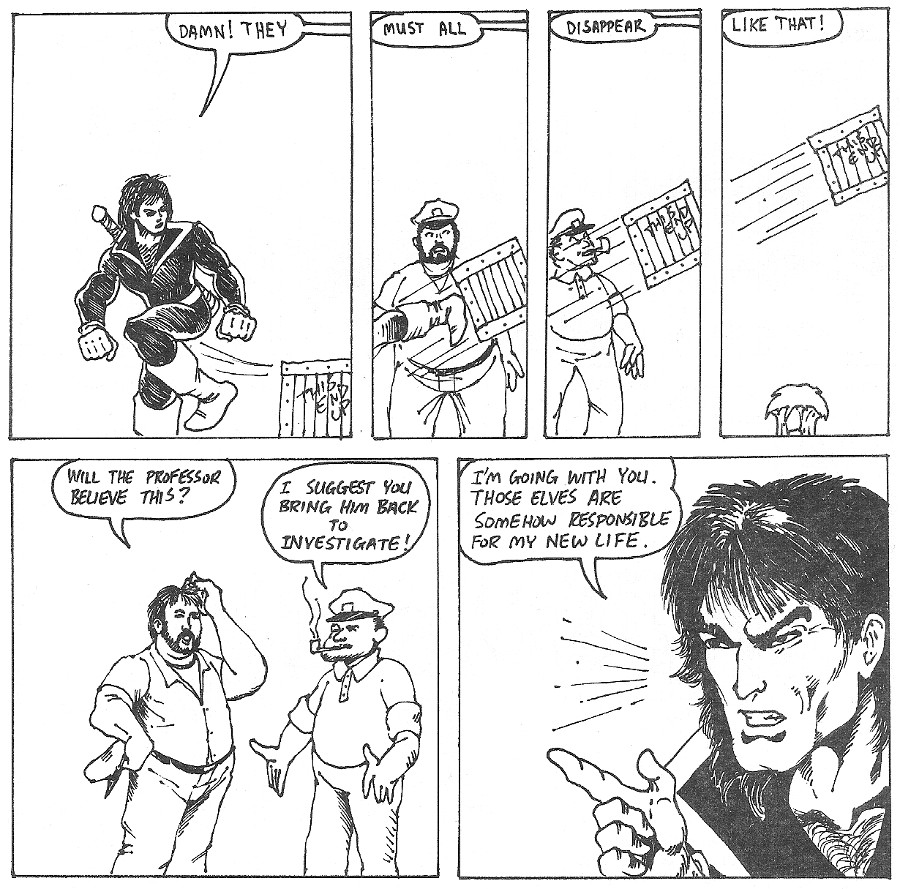

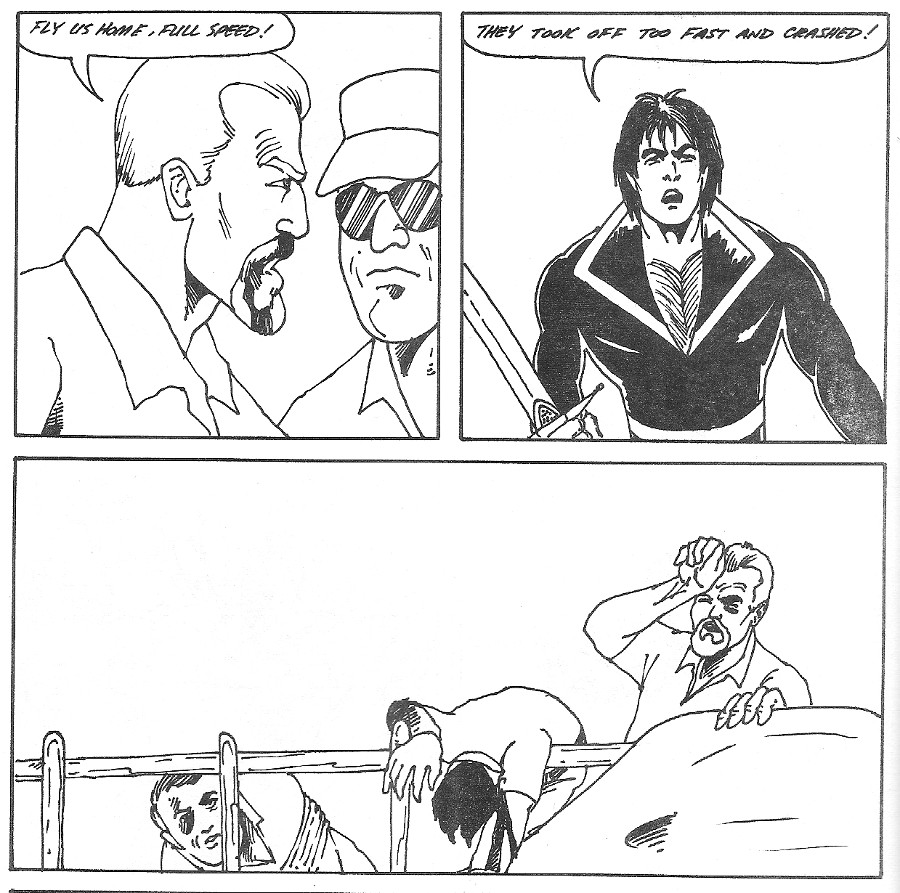

Okay, maybe not respected so much as killed by gangsters and resurrected as a barbarian warrior complete with sword by a little elf-wizard, but whatever. In issue 2, Jontar travels to Temple Island to investigate whether the elf he found in a trashcan is related to the golden elf statues found on the island. There’s a lot of rigamarole involving a female assassin kidnapping an arms dealer and a general leading some private army or something. There are a lot of killings and double-crosses, but none of it makes much sense. In the end, Jontar defeats the bad guys and states that he’s going back to New York to clear his name.

The art by Dane Barrett, as you can tell from the cover above, is not very good. The panels are sparsely filled with clumsy figures over nearly nonexistent backgrounds, although occasionally there is a panel that looks like a decent eighth-grade swipe of somebody like Rich Buckler imitating Adams imitating Kirby, and there are occasional attempts at interesting layouts.

But the funniest moment in the entire comic comes at the big climax. See, one claim comics made all through the 70’s and into the 80’s was that comics had a natural advantage over movies and TV because of production value. Neal Adams or Jack Kirby could dash stuff off in a single panel which would take Hollywood millions of dollars to duplicate, if they could do it at all. But because Dane Barrett was not a good artist, he resorts to the kind of cheap cutaways you often see in low-budget movies to save money.

So what could possibly be historically significant about this comic? Well, it all goes back to the fact that the comics industry in America had by 1986 just emerged from near-demise into a new period of creative excitement and financial profitability with a new wave of creators and the rise of the direct market. But in 1986, when this issue came out, the industry nearly imploded because of books like this. Here’s the deal:

In 1984, Eastman and Laird made a huge splash with their X-Men/Frank Miller parody comic Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Its success, along with the earlier successes of independent black-and-whites like Cerberus and Elfquest, led to a flood of cheap, self-published black-and-white comics on the market by the time Jontar hit the stands. And for a while, they were making huge money, because the low print runs of independent comics made the success stories into instantly rare collector’s items, which lured spectators into the market to buy up a ton of this junk in the hopes that they’d find the next TMNT #1, which led comics shop owners to order every crappy black-and-white comic being released, so they wouldn’t get left out if one happened to hit. It was a cheap, black-and-white tulipmania.

Until a few months later, when people were realizing most of what they were buying was crap like Jontar, which would never be a hit. The speculators dropped out, leaving the comics shops with a ton of unsellable inventory on their shelves, which meant they had no money to order new inventory. Stores went out of business and some smaller publishers, good ones, ended up going bankrupt. And the stores that managed to weather the storm probably ended up doing what my store did, which was to hand me a free copy of Jontar #2 and say, “Do you want this? Because I’m just going to throw it away otherwise.”

And the most incredible part of this entire story? Jontar actually ran for FOUR ISSUES! Seriously.