It should come as no surprise that Frank Miller became a hot property in the aftermath of his success with Batman: The Dark Knight Returns in 1986. What is often forgotten is that, during the same year when Miller’s redefining take on Batman was being released, he was also working at Marvel, having returned to the character who first brought him to prominence. The first half of the year saw Miller as the writer on Daredevil, joining artist David Mazzuchelli on a story that was meant to tear the character down and virtually reboot him, putting him much more in line with the kind of character Miller thought he should be (a reboot that was undone almost completely by the next writer).

It should come as no surprise that Frank Miller became a hot property in the aftermath of his success with Batman: The Dark Knight Returns in 1986. What is often forgotten is that, during the same year when Miller’s redefining take on Batman was being released, he was also working at Marvel, having returned to the character who first brought him to prominence. The first half of the year saw Miller as the writer on Daredevil, joining artist David Mazzuchelli on a story that was meant to tear the character down and virtually reboot him, putting him much more in line with the kind of character Miller thought he should be (a reboot that was undone almost completely by the next writer).

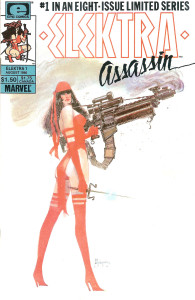

And in the same month that Miller’s final Daredevil issue was published came the first issue of Elektra: Assassin, featuring Daredevil’s former girlfriend who had died in issue #181. Published by Marvel’s prestige Epic Comics imprint, Elektra: Assassin was a sort of prequel, sort of stand-alone non-canon story (much like The Dark Knight Returns) featuring fully painted artwork by newly hot artist Bill Sienkiewicz, fresh from his run on The New Mutants.

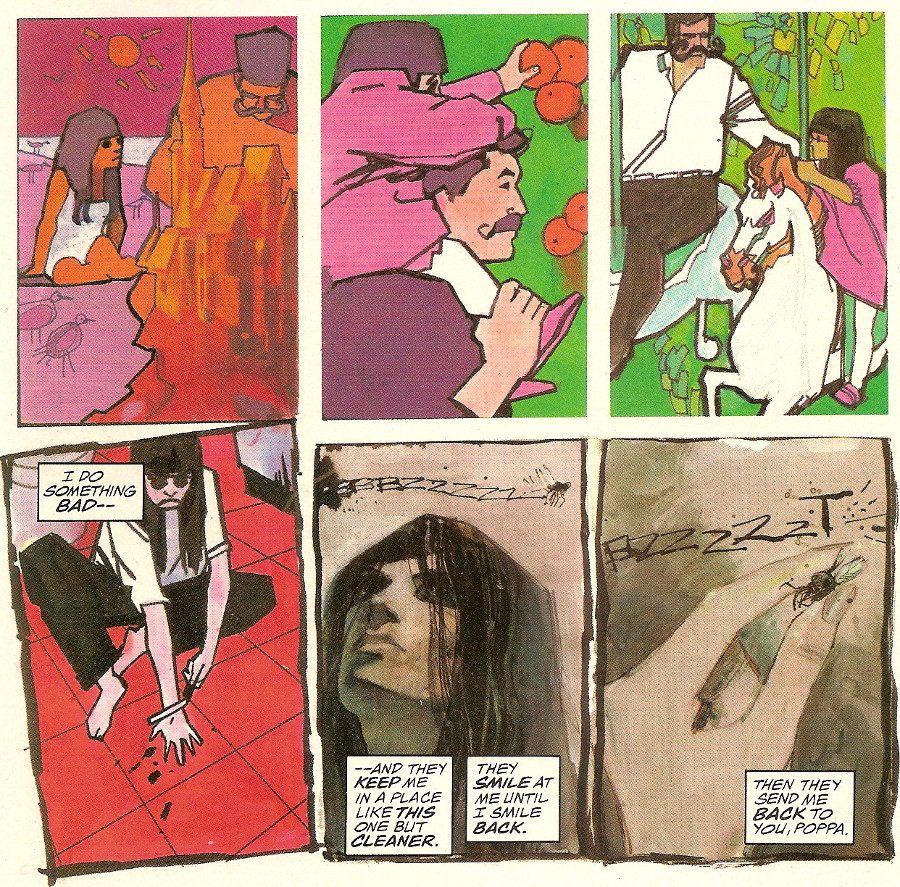

The story opens with an unidentified woman in an insane asylum in South America, reflecting on the tragedies of her life: her mother’s murder, her abusive father, her training by a band of ninja led by Daredevil’s mentor Stick, her subsequent corruption and pledge to follow a dark figure known only as the Beast. The Beast leads the ninja clan known as the Hand, whom Elektra later rebels against. Sienkiewicz’s artwork, which had gone through an experimental phase on New Mutants that turned off as many fans as it excited, got even more way out here. Given free reign by Marvel and Miller, Sienkiewicz took a very impressionistic approach. For instance, in the first issue, he illustrates Elektra’s memories in a colorful storybook fashion to contrast with her drab imprisonment in the asylum.

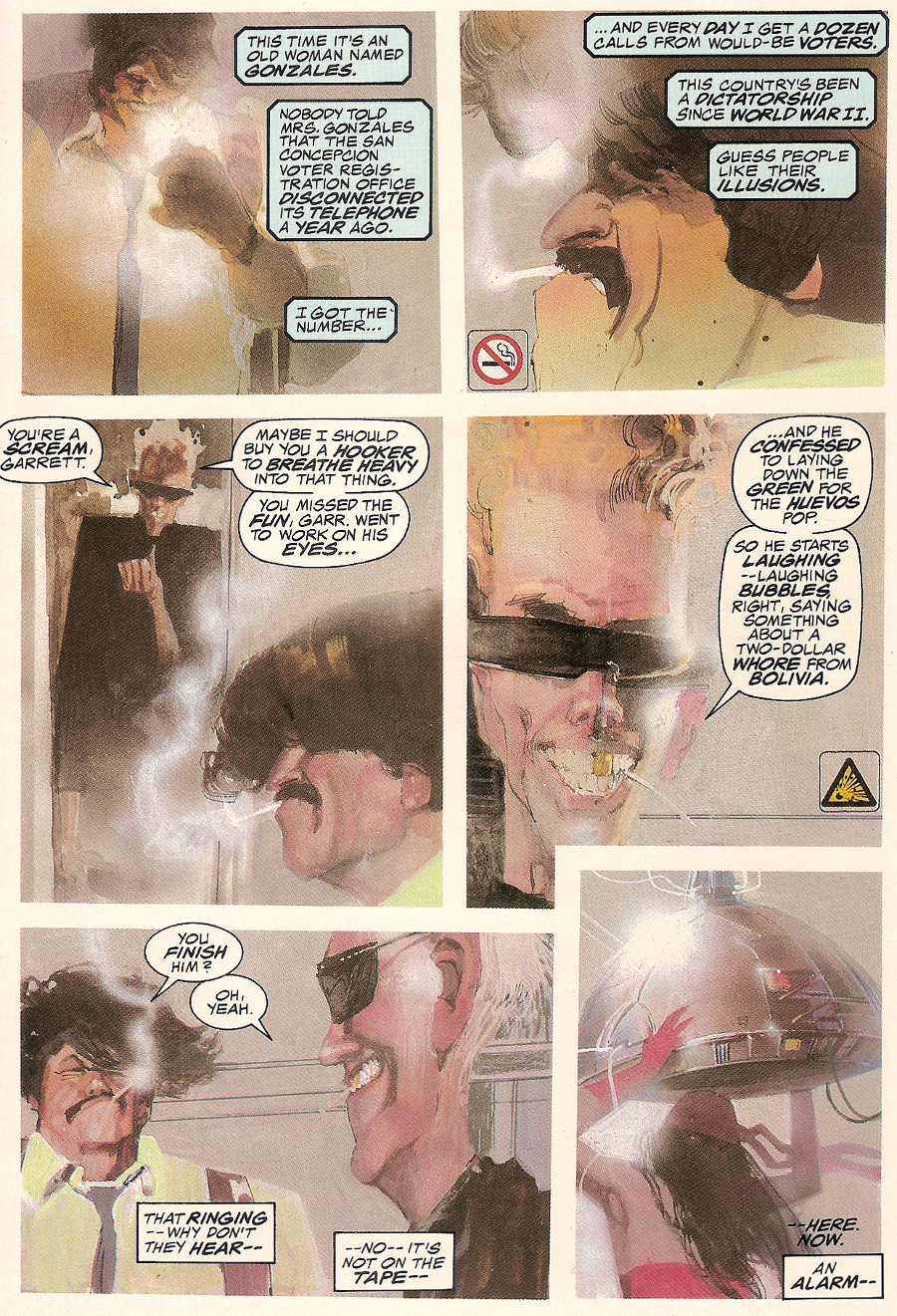

Elektra ends up escaping from the asylum (it turns out she was just pretending to be held there as part of a plot to kill a South American dictator possessed by the spirit of the Beast). She then ends up in the custody of S.H.I.E.L.D. thanks to agents Garrett and Perry. Garrett is a thoroughly unlikeable, cynical fellow who happens to be something like 90% cyborg, but he has a buried streak of idealism underneath. Perry, on the other hand, is simply a psychopath.

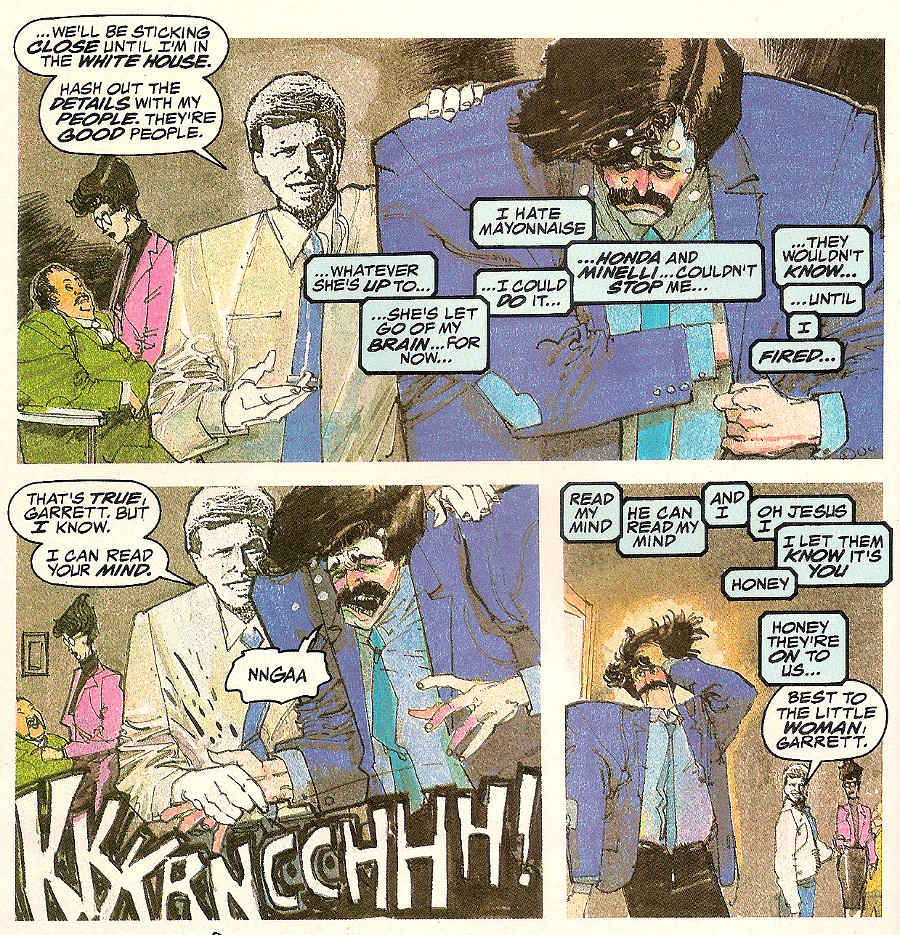

Elektra kills Perry and escapes with Garrett, who becomes her semi-unwilling partner in a quest to stop American presidential candidate Ken Wind. Ken Wind, you see, has been taken over by the Beast, who plans to start a nuclear holocaust once Wind is elected President. In order to save the world, Elektra and Garrett must battle not only the Beast and his Hand minions, including psychotic ex-partner Perry resurrected as a nearly invincible cyborg,, but also the forces of S.H.I.E.L.D. led by Nick Fury and agent Chastity McBride. Sienkiewicz depicts Wind as a Robert Kennedy lookalike, with his photocopied face never changing expression and always facing the reader, even when his back is turned.

At the time, Miller’s fragmentary stream-of-consciousness narration and satirical storyline combined with Sienkiewicz’s boldly experimental artwork seemed daring and dangerous. Looking back at it now, it seems as if it’s the first step in Miller’s subsequent downward spiral. Most of the problems of Miller’s later work–unpleasant characters, confusing storytelling, muddled political satire–are present here. I was willing to overlook them then, because The Dark Knight Returns had seemed so bold, and Miller was experimenting, searching for his path. I figured he would continue to build on his strengths and work through his weaknesses. I had no idea then that his later work would continue to magnify the things I liked least about Elektra: Assassin.